The Case for an Anti-Productive AI

Putting the "artificial" in artificial intelligence

The tweet thread began in exactly the way you'd predict:

The thread continued with tips like "set a 'no-internet' day once a week," and "make a to-don't list" that "includes things you shouldn't do, no matter what."

24 hours, thousands of likes and retweets, and over a million impressions later, the thread's author Ali Abdaal revealed the catch: all of the advice was written by AI using a service called Lex.

There was humor in this exchange, sure, but who was the joke on? On the audience that fell for the prank and thought the thread was written by a human (as was implied)? On the industry of thinkfluencers whose tweets are so generic and memeable that they are ripe for forgery? On Abdaal himself, whose labor has been successfully supplanted by automation? Or more broadly, on the modern reification of productivity as the messianic north star for surviving and thriving in the global economy?

For decades, science fiction has warned of an impending singularity, in which AI advances so far that we lose control over it—its progress both inevitable and irreversible. But fixating on our fear of future singularity has ushered in an even more insidious present. You could even say that we are currently gaining unprecedented control over our tools. With just a few lines of text we can generate images that have never existed before in infinite styles and without any technical training. We can compose essays, Twitter threads, or recipes on the go, on a whim, and on a budget.

We are careening towards a future in which each of us is a feudal lord over a staff of AIs, a wealthy patron of the arts commanding the artist we hold in our pockets to compose a symphony in split seconds.

But god-adjacent control over tools has always led to a different, more nefarious loss of control. Our history is riddled with examples of tools that were supposed to save us time—cars, dishwashers, workplace communication tools—that instead propelled us towards more responsibility and less leisure time.

And we may be building towards that history’s apotheosis. As I write this paragraph, my finger twitches autonomously towards tools that claim to save me time. I know the above paragraph to be true from both lived experience and data-backed evidence that I have encountered in the past. But instead of browsing my memories or bookshelves for help, I tab over to Metaphor, an AI tool that responds to questions with hyperlinks, and prompt it to do my research for me.

Through Metaphor's dutiful responses, I encounter some arguments I have seen before and others I have not. I am directed to Ruth Schwartz Cohen's 1983 book on housework titled More Work for Mother, which gives countless examples of technologies with a counterintuitive influence on time, including the eggbeater, which made it easier for women to bake cakes, but ushered in the popularity of angel food cakes, "in which eggs are the only leavening, and yolks and whites are beaten separately—thus doubling the work."

Did using Metaphor as my research assistant take me less time than it would have otherwise? I'm not sure. But if it did, will I spend that time on leisure, or on more work? In his 1918 The Instinct of Workmanship (also found through Metaphor), economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen argued that "each new expedient added to and incorporated in the system offers not only a new means of keeping up with the run of things at an accelerated pace but also a new chance of getting left out of the running...any technological advantage gained by one competitor forthwith becomes a necessity to all the rest, on pain of defeat."

In a world in which we are forced to segment every fiber of our being into monetizable chunks, our tools become nothing more than weapons in the arms race for productivity and attention. Veblen drew a direct parallel between the seemingly quainter advancements at the turn of the 20th century (the typewriter and telephone, for example) and advancements in the technology of warfare. It's only natural that we're approaching the logical conclusion of this pattern. What better way to maximize our output than to radically dissociate from it?

But there is an alternative, if unlikely, future for AI. We can reclaim it as a tool for slowing down. Rather than making AI work for us, we can use it to pay attention, connect with each other, and deepen our sense of place.

And this may be the best time to imagine that speculative future. We still reside in an uncanny valley wherein the tools are just powerful enough to serve as useful toys, but flawed enough that they still surprise us and invoke our sense of wonder.

By way of example, here are suggestions for how to misuse three buzzworthy AI tools to achieve these goals:

Lex

What is it?

A word processor with an AI assistant baked in that aims to help you write faster.

Intended use case (productive): writing

Use to draft text for a school term paper, blog post, or Twitter thread and pass it off as written by a human.

Speculative use case (anti-productive): connecting

Pair up with a friend you feel close to but haven't been in touch with for a while. Begin a correspondence over snail mail (preferred) or email in which at least 80% of the text is written by Lex's AI but all of it rings true. Indicate which text was written by an AI by using a different color. Continue to keep in touch, gradually reducing your reliance on the AI over time.

DALL•E

What is it?

A diffusion-powered image generator trained on billions of images that can create realistic images based on a text prompt in any style.

Intended use case (productive): producing images

Generate an image to promote your product on social media

Speculative use case (anti-productive): looking

You are a Renaissance artist learning the art by imitating its masters. Select an existing image from the Archillect Instagram account. Stare at it like you are staring at a still life, taking in as many details as possible in an attempt to understand its all of its layers. Then using DALL•E, reproduce the image as precisely as possible using only text prompts.

Metaphor

What is it?

An AI search engine that takes in a text prompt and tries to predict what links would likely follow that prompt on a webpage.

Intended use case (productive): searching

Find a specific answer to a question you have.

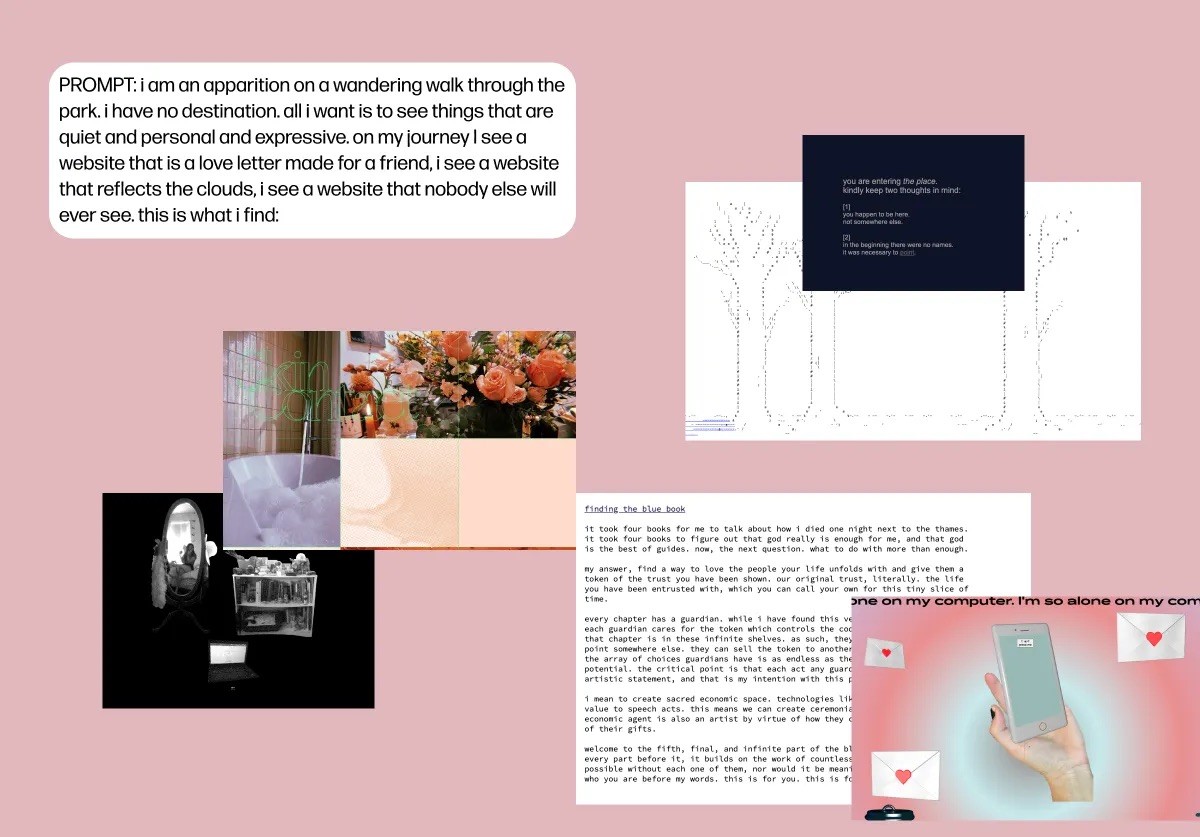

Speculative use case (anti-productive): wandering

Wander: Write a poetic prompt about a journey you are on and what you see along the way. Enter it into the search box and browse through the results with a curious eye. Make a journal with some of the things you find.

Nov 30, 2022

·

6 min read

The Case for an Anti-Productive AI

Putting the "artificial" in artificial intelligence

The tweet thread began in exactly the way you'd predict:

The thread continued with tips like "set a 'no-internet' day once a week," and "make a to-don't list" that "includes things you shouldn't do, no matter what."

24 hours, thousands of likes and retweets, and over a million impressions later, the thread's author Ali Abdaal revealed the catch: all of the advice was written by AI using a service called Lex.

There was humor in this exchange, sure, but who was the joke on? On the audience that fell for the prank and thought the thread was written by a human (as was implied)? On the industry of thinkfluencers whose tweets are so generic and memeable that they are ripe for forgery? On Abdaal himself, whose labor has been successfully supplanted by automation? Or more broadly, on the modern reification of productivity as the messianic north star for surviving and thriving in the global economy?

For decades, science fiction has warned of an impending singularity, in which AI advances so far that we lose control over it—its progress both inevitable and irreversible. But fixating on our fear of future singularity has ushered in an even more insidious present. You could even say that we are currently gaining unprecedented control over our tools. With just a few lines of text we can generate images that have never existed before in infinite styles and without any technical training. We can compose essays, Twitter threads, or recipes on the go, on a whim, and on a budget.

We are careening towards a future in which each of us is a feudal lord over a staff of AIs, a wealthy patron of the arts commanding the artist we hold in our pockets to compose a symphony in split seconds.

But god-adjacent control over tools has always led to a different, more nefarious loss of control. Our history is riddled with examples of tools that were supposed to save us time—cars, dishwashers, workplace communication tools—that instead propelled us towards more responsibility and less leisure time.

And we may be building towards that history’s apotheosis. As I write this paragraph, my finger twitches autonomously towards tools that claim to save me time. I know the above paragraph to be true from both lived experience and data-backed evidence that I have encountered in the past. But instead of browsing my memories or bookshelves for help, I tab over to Metaphor, an AI tool that responds to questions with hyperlinks, and prompt it to do my research for me.

Through Metaphor's dutiful responses, I encounter some arguments I have seen before and others I have not. I am directed to Ruth Schwartz Cohen's 1983 book on housework titled More Work for Mother, which gives countless examples of technologies with a counterintuitive influence on time, including the eggbeater, which made it easier for women to bake cakes, but ushered in the popularity of angel food cakes, "in which eggs are the only leavening, and yolks and whites are beaten separately—thus doubling the work."

Did using Metaphor as my research assistant take me less time than it would have otherwise? I'm not sure. But if it did, will I spend that time on leisure, or on more work? In his 1918 The Instinct of Workmanship (also found through Metaphor), economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen argued that "each new expedient added to and incorporated in the system offers not only a new means of keeping up with the run of things at an accelerated pace but also a new chance of getting left out of the running...any technological advantage gained by one competitor forthwith becomes a necessity to all the rest, on pain of defeat."

In a world in which we are forced to segment every fiber of our being into monetizable chunks, our tools become nothing more than weapons in the arms race for productivity and attention. Veblen drew a direct parallel between the seemingly quainter advancements at the turn of the 20th century (the typewriter and telephone, for example) and advancements in the technology of warfare. It's only natural that we're approaching the logical conclusion of this pattern. What better way to maximize our output than to radically dissociate from it?

But there is an alternative, if unlikely, future for AI. We can reclaim it as a tool for slowing down. Rather than making AI work for us, we can use it to pay attention, connect with each other, and deepen our sense of place.

And this may be the best time to imagine that speculative future. We still reside in an uncanny valley wherein the tools are just powerful enough to serve as useful toys, but flawed enough that they still surprise us and invoke our sense of wonder.

By way of example, here are suggestions for how to misuse three buzzworthy AI tools to achieve these goals:

Lex

What is it?

A word processor with an AI assistant baked in that aims to help you write faster.

Intended use case (productive): writing

Use to draft text for a school term paper, blog post, or Twitter thread and pass it off as written by a human.

Speculative use case (anti-productive): connecting

Pair up with a friend you feel close to but haven't been in touch with for a while. Begin a correspondence over snail mail (preferred) or email in which at least 80% of the text is written by Lex's AI but all of it rings true. Indicate which text was written by an AI by using a different color. Continue to keep in touch, gradually reducing your reliance on the AI over time.

DALL•E

What is it?

A diffusion-powered image generator trained on billions of images that can create realistic images based on a text prompt in any style.

Intended use case (productive): producing images

Generate an image to promote your product on social media

Speculative use case (anti-productive): looking

You are a Renaissance artist learning the art by imitating its masters. Select an existing image from the Archillect Instagram account. Stare at it like you are staring at a still life, taking in as many details as possible in an attempt to understand its all of its layers. Then using DALL•E, reproduce the image as precisely as possible using only text prompts.

Metaphor

What is it?

An AI search engine that takes in a text prompt and tries to predict what links would likely follow that prompt on a webpage.

Intended use case (productive): searching

Find a specific answer to a question you have.

Speculative use case (anti-productive): wandering

Wander: Write a poetic prompt about a journey you are on and what you see along the way. Enter it into the search box and browse through the results with a curious eye. Make a journal with some of the things you find.

Nov 30, 2022

·

6 min read

The Case for an Anti-Productive AI

Putting the "artificial" in artificial intelligence

The tweet thread began in exactly the way you'd predict:

The thread continued with tips like "set a 'no-internet' day once a week," and "make a to-don't list" that "includes things you shouldn't do, no matter what."

24 hours, thousands of likes and retweets, and over a million impressions later, the thread's author Ali Abdaal revealed the catch: all of the advice was written by AI using a service called Lex.

There was humor in this exchange, sure, but who was the joke on? On the audience that fell for the prank and thought the thread was written by a human (as was implied)? On the industry of thinkfluencers whose tweets are so generic and memeable that they are ripe for forgery? On Abdaal himself, whose labor has been successfully supplanted by automation? Or more broadly, on the modern reification of productivity as the messianic north star for surviving and thriving in the global economy?

For decades, science fiction has warned of an impending singularity, in which AI advances so far that we lose control over it—its progress both inevitable and irreversible. But fixating on our fear of future singularity has ushered in an even more insidious present. You could even say that we are currently gaining unprecedented control over our tools. With just a few lines of text we can generate images that have never existed before in infinite styles and without any technical training. We can compose essays, Twitter threads, or recipes on the go, on a whim, and on a budget.

We are careening towards a future in which each of us is a feudal lord over a staff of AIs, a wealthy patron of the arts commanding the artist we hold in our pockets to compose a symphony in split seconds.

But god-adjacent control over tools has always led to a different, more nefarious loss of control. Our history is riddled with examples of tools that were supposed to save us time—cars, dishwashers, workplace communication tools—that instead propelled us towards more responsibility and less leisure time.

And we may be building towards that history’s apotheosis. As I write this paragraph, my finger twitches autonomously towards tools that claim to save me time. I know the above paragraph to be true from both lived experience and data-backed evidence that I have encountered in the past. But instead of browsing my memories or bookshelves for help, I tab over to Metaphor, an AI tool that responds to questions with hyperlinks, and prompt it to do my research for me.

Through Metaphor's dutiful responses, I encounter some arguments I have seen before and others I have not. I am directed to Ruth Schwartz Cohen's 1983 book on housework titled More Work for Mother, which gives countless examples of technologies with a counterintuitive influence on time, including the eggbeater, which made it easier for women to bake cakes, but ushered in the popularity of angel food cakes, "in which eggs are the only leavening, and yolks and whites are beaten separately—thus doubling the work."

Did using Metaphor as my research assistant take me less time than it would have otherwise? I'm not sure. But if it did, will I spend that time on leisure, or on more work? In his 1918 The Instinct of Workmanship (also found through Metaphor), economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen argued that "each new expedient added to and incorporated in the system offers not only a new means of keeping up with the run of things at an accelerated pace but also a new chance of getting left out of the running...any technological advantage gained by one competitor forthwith becomes a necessity to all the rest, on pain of defeat."

In a world in which we are forced to segment every fiber of our being into monetizable chunks, our tools become nothing more than weapons in the arms race for productivity and attention. Veblen drew a direct parallel between the seemingly quainter advancements at the turn of the 20th century (the typewriter and telephone, for example) and advancements in the technology of warfare. It's only natural that we're approaching the logical conclusion of this pattern. What better way to maximize our output than to radically dissociate from it?

But there is an alternative, if unlikely, future for AI. We can reclaim it as a tool for slowing down. Rather than making AI work for us, we can use it to pay attention, connect with each other, and deepen our sense of place.

And this may be the best time to imagine that speculative future. We still reside in an uncanny valley wherein the tools are just powerful enough to serve as useful toys, but flawed enough that they still surprise us and invoke our sense of wonder.

By way of example, here are suggestions for how to misuse three buzzworthy AI tools to achieve these goals:

Lex

What is it?

A word processor with an AI assistant baked in that aims to help you write faster.

Intended use case (productive): writing

Use to draft text for a school term paper, blog post, or Twitter thread and pass it off as written by a human.

Speculative use case (anti-productive): connecting

Pair up with a friend you feel close to but haven't been in touch with for a while. Begin a correspondence over snail mail (preferred) or email in which at least 80% of the text is written by Lex's AI but all of it rings true. Indicate which text was written by an AI by using a different color. Continue to keep in touch, gradually reducing your reliance on the AI over time.

DALL•E

What is it?

A diffusion-powered image generator trained on billions of images that can create realistic images based on a text prompt in any style.

Intended use case (productive): producing images

Generate an image to promote your product on social media

Speculative use case (anti-productive): looking

You are a Renaissance artist learning the art by imitating its masters. Select an existing image from the Archillect Instagram account. Stare at it like you are staring at a still life, taking in as many details as possible in an attempt to understand its all of its layers. Then using DALL•E, reproduce the image as precisely as possible using only text prompts.

Metaphor

What is it?

An AI search engine that takes in a text prompt and tries to predict what links would likely follow that prompt on a webpage.

Intended use case (productive): searching

Find a specific answer to a question you have.

Speculative use case (anti-productive): wandering

Wander: Write a poetic prompt about a journey you are on and what you see along the way. Enter it into the search box and browse through the results with a curious eye. Make a journal with some of the things you find.

Nov 30, 2022

·

6 min read

Lens in your inbox

Lens features creator stories that inspire, inform, and entertain.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter so you never miss a story.

Lens in your inbox

Lens features creator stories that inspire, inform, and entertain.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter so you never miss a story.

Lens in your inbox

Lens features creator stories that inspire, inform, and entertain.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter so you never miss a story.